With European Member States finding a political agreement over delaying the deadlines for implementation of the European Union’s sixth Directive on Administrative Cooperation in the field of taxation (more succinctly DAC6), Antonello Argenziano provides an update on the implications of the directive and the challenges facing the market.

While EU Member States have been rushing to get domestic legislation implementing DAC6 onto their statute books, there’s an even bigger rush to comply for the targets of the legislation – intermediaries, which can be individuals or companies and include lawyers, accountants, corporate service providers, banks, holding companies and group treasury entities.

Up until a few weeks ago, the industry was working towards an implementation date of 1 July, giving firms just two months to complete preparation of two years’ worth of retrospective reporting on transactions, in accordance with legislation in place for barely months, and in some cases weeks, and that varies, sometimes significantly , from country to country.

However, the tight timetable is now set to be relaxed for at least some EU Member States, following an initiative by the European Commission – now endorsed by permanent representatives – to extend the implementation deadlines by six months, reflecting the difficulty faced by firms as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic. It remains to be seen how many countries take advantage of the additional leeway. Belgium, Luxembourg and Sweden have already announced that they will do so, while the UK authorities communicated that they intend to wait until “the proposals are finalised” before confirming their stand on the deferral of the reporting deadlines.

Under the original directive, as of 1 July intermediaries would have just two months to complete preparation of two years’ worth of retrospective reporting on transactions

The directive will require compulsory reporting by EU intermediaries to their domestic tax authority of cross-border transactions or arrangements involving one or more EU member states that exhibit so-called hallmarks of aggressive tax avoidance. Where no EU intermediary is involved, or if they assert a legal duty of confidentiality, which applies notably but not exclusively to lawyers, the burden of reporting falls to any or all EU taxpayers involved in the arrangement.

Even before the pandemic led to economic shutdowns across Europe, there was concern about Member States’ tardiness in adopting the legislation, in the light of the retrospective reporting obligation that the directive imposes on intermediaries.

The deadline for transposition of the directive into national law, 1 January, was missed by seven of the then 28-Member States. As of the end of May, Greece had still not even published draft legislation. Luxembourg was also one of the laggards, even though the government placed a draft bill before the Chamber of Deputies on 8 August 2019. After amendments to meet concern about professional confidentiality requirements, it was finally approved by parliament on 21 March and received royal assent four days later.

Deadline extension

Following a proposal by the Commission for an amending directive to push back the DAC6 deadlines, on 3 June the Committee of Permanent Representatives of EU Member States reached agreement on an optional six-month delay to the implementation timetable. On 5 June, a report by the Economic and Financial Affairs Council (ECOFIN) indicated that it’s expected that the draft Directive will be adopted by the European Council before 1 July.

Following such approval by the European Council, which at this point is expected to be a formality, European Member States opting for the delay will have to adopt the changes into their national law.

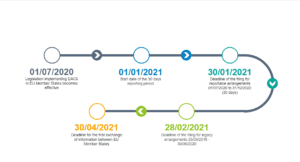

Under the proposal, the 30-day reporting period for cross-border arrangements implemented between 1 July and 31 December would start on 1 January 2021, while the deadline for reporting of ‘historic’ cross-border arrangements (between 25 June 2018 and 30 June 2020) would shift from 31 August 2020 to 28 February 2021. At the same time, the date for the first exchange of information between countries on reportable cross-border arrangements would be deferred from 31 October 2020 to 30 April 2021.

Whether or not intermediaries (and taxpayers) will benefit from the deferral of reporting requirements will depend on the approach taken by different EU Member States. Belgium, Luxembourg and Sweden announced they’d take advantage of the delay option shortly after the decision of the permanent representatives. Other countries have expected to follow suit, since those that don’t do so risk being inundated by default with reports on cross-border arrangements between countries of which one has deferred, and the other has not.

Hallmarks

The legislation is part of a growing trend at European and national level to clamp down on transactions that aren’t in themselves illegal, unlike outright tax evasion, but that may have been designed artificially to reduce the tax liability of one or more parties to the transaction or arrangement.

The fact that an arrangement is reportable doesn’t mean that tax avoidance has been proven, simply that national tax authorities have grounds for examining whether it exceeds legal thresholds for permissible tax efficiency.

The directive sets out a total of 15 hallmarks in five categories that make an arrangement reportable:

1. Generic hallmarks linked to the main benefit test (whether one of the principal purposes of the arrangement is to obtain a tax benefit)

2. Specific hallmarks linked to the main benefit test

3. Specific hallmarks related to cross-border transactions

4. Specific hallmarks concerning automatic exchange of information and beneficial ownership, and

5. Specific hallmarks concerning transfer pricing

These hallmarks or characteristics include confidentiality agreements regarding tax advantages, intermediary fees contingent on tax benefits, or standardised documentation or structures that aren’t tailored to a participant’s individual circumstances.

Other hallmarks that may indicate aggressive tax avoidance include buying of loss-making entities to reduce tax liability, the conversion of income to capital, gifts or other types of revenue taxable at a lower rate, round-trip transactions, and deductible cross-border payments involving no- or low-tax jurisdictions or that benefit from other preferential regimes.

The legislation also highlights double tax deductions or relief, transactions that sidestep exchange of information and beneficial ownership reporting obligations, and transfer pricing involving hard-to-value intangible assets or transactions that have the effect of lowering taxable profit in the future.

Under the original timetable, all relevant cross-border arrangements established since the directive became law, between 25 June 2018 and 30 June 2020, were due to be reported by 31 August (arrangements implemented during July were to be reported within 30 days). Information reported to national tax authorities was to begin to be exchanged with other EU Member States on 31 October.

Differences in national implementation

On top of these uncertain deadlines, the complications for intermediaries include the fact that legislation in the form of directives offers EU Member States some leeway in how they’re transposed into national law. For instance, the EU text doesn’t define what constitutes an “arrangement” or a “tax advantage”, but member states are free to do so, as Ireland has done, as long as the result doesn’t limit the scope of the directive.

Other variations include, for example, a provision in the Dutch legislation specifying that companies in the same group as a taxpayer may be considered an intermediary if it performs tax functions for the group.

French intermediaries are exempt from reporting on arrangements involving their permanent establishments abroad.

Luxembourg’s legislation considers the country’s statutory professional privilege, providing an exemption from reporting not only to lawyers but also to chartered accountants and to auditors.

Unlike the directive, Germany’s legislation doesn’t distinguish between promoters and service providers giving aid, assistance or advice regarding a cross-border arrangement. This will place a reporting obligation on intermediaries with a German nexus – such as a head office or centre of management, or the German permanent establishment of a non-EU intermediary – no matter where the taxpayer is resident, or where the tax advantage is derived.

Poland, which exceptionally brought its domestic legislation into force on 1 January this year, has significantly enlarged its scope to include domestic arrangements and all taxes, and it also defines hallmarks more expansively than the EU directive. Portugal has added value-added tax to the scope, and legislation there and in Sweden also covers domestic arrangements.

Concerns facing intermediaries include their need for specialist expertise in tracking variations in the law from country to country

In conclusion

In conclusion, the concerns facing intermediaries include the need for specialist expertise to track variations in the law from country to country, as well as the potentially large number of retrospective transactions or arrangements that must be reviewed in a short time – knowing that clients won’t thank them for over-reporting that could prompt tax authorities to pick over the details of blameless transactions.

Facing a short time to adapt to new legislation (which may yet need further regulatory clarification or guidance), intermediaries face a heavy administrative burden to fulfil the requirements on time and without error. The penalties for non-compliance are heavy, running as high as €5 million in Poland and €250,000 in Luxembourg, and even inadvertent mistakes in reporting are liable to be costly.

The industry is now looking for certainty over the approval of the newly proposed deadlines (in the table below) and asking for a consistent approach in the adoption of the Directive across EU Member States.

Many firms are likely to seek external help in meeting the challenge. This will involve, at a minimum, multi-jurisdictional support that brings understanding of local requirements, provided by firms with well-established processes and operational functions to help intermediaries avoid the risk of penalties. Additionally, it will involve the use of proven technology to shoulder what may be a substantial administrative burden.

Many firms are likely to seek external help to meet the challenge, including proven technology to shoulder what may be a substantial administrative burden

The proposed extension to the reporting timetable, for at least some intermediaries, don’t do much to relieve the burden on industry practitioners as the hard work gears up to a new level.

To find out more about DAC6 and how we can help, please get in touch.